Dear bookseller,

I am enormously excited to bring you Babel, also known as Babel: An Arcane History, also known as Babel, or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translator’s Revolution. The public reason for the three long and unwieldy titles is that we wanted to imitate the long titles of Victorian titles; the other reason is that my editors and I could not stop arguing about the metadata, so in the end we decided to have our cake and eat it too.

Every time I asked, “Can we do this crazy experimental formal thing?” my editors responded with, “Why not?”

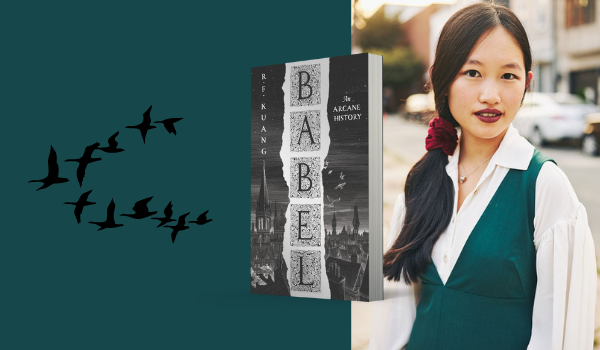

R.F. Kuang

This indulgence in maximalist formal splendor is really symptomatic of our entire approach to this novel. Babel includes lengthy epigrams by authors ranging from Plato to Fanon; footnotes upon footnotes; and even in one chapter a newspaper cutting which then became a newspaper cutting inside the footnote at my insistence. (I wanted to use that footnote especially to highlight the way the suffering of colonized peoples has so often been relegated to the footnotes of British imperial histories. You’ll know it when you see it.) Every time I asked, “Can we do this crazy experimental formal thing?” my editors responded with, “Why not?” (It’s hard to distinguish between enthusiasm and exasperation over email.) At some point we decided our attitude to any proposed “cool factor” would just be to go for it. Hence the cover, dripping in silver foil.

We wanted, at the end of the day, to create a proper doorstopper of a book– one that rewards you for diving in with a veritable feast of allusions, easter eggs, and wordplay. Babel involves a full-throttled grappling with Victorian history and literature–the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Babel, I hope, has taken all the threads of Victorian fiction and spun them together to make something new.

R.F. Kuang

I did an interview earlier this week where I was asked why the novel begins with a lengthy author’s note on my representations of Oxford and England if the first chapter proceeds to drop the reader in Canton, China. The answer is that Babel seeks to represent the Victorian England for the truly global and cosmopolitan place it was. Victorians were sailing to China all the time! When we think of Victorian novels we tend to think of parochial, domestic dramas; of ballrooms and narrow alleys and bridges across the Thames.

But in the 1830s, it was impossible to get through an afternoon tea without using words and goods–sugar, coffee, porcelain–brought back through colonial trade networks spanning the globe. And it was impossible to walk through London’s streets without hearing seeing a variety of faces; hearing a variety of languages and dialects and regional accents. Why, then, should our fiction about that era center on the same kinds of subjects over and over again?

Babel is not so much an intervention against the Victorian canon as it wholly embraces it – all its rhetorical flourishes and narrative tropes and ideological biases. I don’t believe in casting out the old, but I love adding previously unheard voices into the mix. Babel, I hope, has taken all the threads of Victorian fiction and spun them together to make something new. I can’t wait to see it on shelves.

Love,

Rebecca